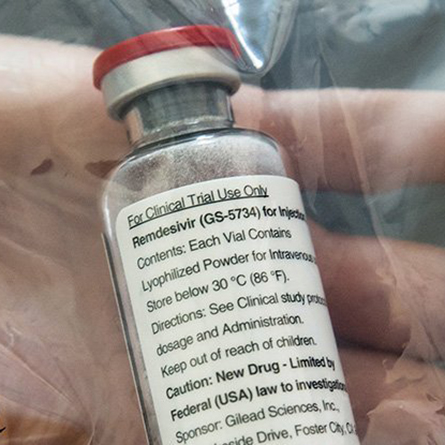

Remdesivir becomes first drug to show clear-cut effect in treating COVID-19

Susan Guillet ’94 is director of clinical operations oncology at Gilead Sciences, Inc., the biotech that developed the drug remdesivir, the first drug to show a clear-cut effect in treating COVID-19, according to Dr. Anthony Fauci, who heads the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Guillet and her team now work in six hour shifts on processing individual requests for compassionate use of remdesivir, and then return to their routine responsibilities of managing oncology trials, which still need to proceed within specified timelines.

“We are pulling in all hands on deck because we want to process as many requests for remdesivir as possible,” said Guillet.

Production of the drug is kicking into high gear. Gilead now has 1.5 million doses, which is enough for 140,000 patients. The company is working with partners around the world to boost its manufacturing. Its goal is to produce more than 500,000 treatment courses by October and more than 1 million treatment courses by the end of this year.

It will be needed, because Dr. Fauci told reporters at the White House on April 29 that “the data shows that remdesivir has a clear-cut, significant, positive effect in diminishing the time to recovery." On May 1, the Food and Drug Administration issued an emergency approval for remdesivir as a treatment for patients severely ill with COVID-19.

The research that led to remdesivir began as early as 2009, through trials under way at the time to fight hepatitis C and respiratory syncytial virus. During the Ebola outbreak, remdesivir showed efficacy in blocking the Ebola virus in rhesus monkeys. Under “compassionate use” protocols, a small number of Ebola patients received the drug. While the drug proved less effective than others against Ebola, the research established its safety profile. Subsequent trials showed antiviral activity against MERS and SARS, both coronaviruses said to be structurally similar to COVID-19.

In the U.S., remdesivir first showed signs as a potential therapeutic for COVID-19 in January. A patient who had just returned from Wuhan, China, where the coronavirus is said to have originated, checked into Providence Regional Medical Center in Everett, Washington, on Jan. 20. He developed pneumonia and required oxygen. With his health failing, doctors intravenously administered remdesivir. The patient quickly improved and requests for the drug began.

“Finding patients for clinical trials can be difficult. But in this case, we’re having no problem finding patients willing to enter the Gilead-sponsored trials and we don’t want to turn anyone down,” Guillet said.

Very quickly trials were set up across the world, some in Wuhan, some here in the U.S. at Gilead and some run by the NIAID. Some of these trials were non-randomized while others were randomized, meaning some patients receive remdesivir while others receive a placebo.

“Data from controlled clinical trials are required to prove both safety and efficacy,” Guillet said, adding that proper dosing also needs to be worked out. “We are conducting randomized trials in patients across different demographics and varying symptoms: those in critical condition (on ventilators), patients in severe condition where they need oxygen support and patients who are in moderate condition.”

Remdesivir works by blocking the virus’s ability to replicate. The drug is designed to interfere with an enzyme the virus uses to copy its RNA genome, rendering the coronavirus unable to infect other cells. Trials are still ongoing. And while some trials have had mixed results, the randomized trial overseen by NIAID showed that patients on the drug had a 31 percent faster time to recovery than those on a placebo.

“Specifically, the median time to recovery was 11 days for patients treated with remdesivir compared with 15 days for those who received placebo,” the study revealed.

Fauci added, “Although a 31 percent improvement doesn’t seem like a knockout 100 percent, it is a very important proof of concept, because what it has proven is that a drug can block this virus.”

Guillet majored in political science and never dreamed she’d end up in the field of science.

“People in my field look at my resume all the time and can’t believe I was a liberal arts student,” she said. “As a project manager of trials, I need a science background to understand the trials but also good people skills to communicate with scientists and doctors who run our studies.”