A magazine published three times a year by the College and mailed free of charge to all alumni, parents and friends of the College.

Conn joins Connecticut Space Grant Consortium

Professor Shou Ping Liu has the Connecticut College Orchestra going places

August in Pictures

Tribal remains discovered on Conn grounds repatriated after four decades

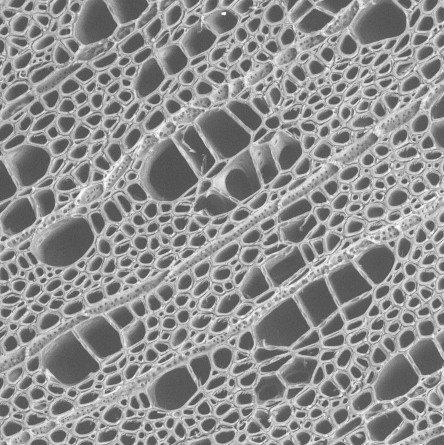

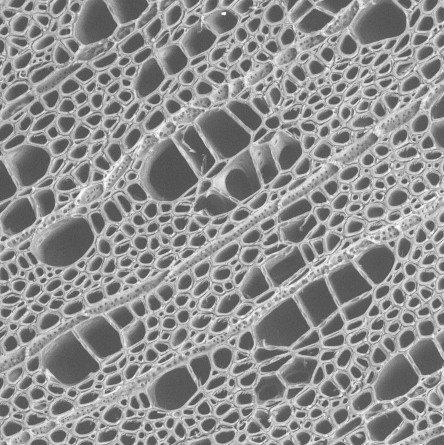

Conn awarded $251K NSF grant for a new scanning electron microscope

‘Courage to care:’ Academic year begins with 110th Convocation

Conn welcomes Class of 2028

Five join Conn’s Board of Trustees; Seth Alvord ’93 elected chair

July in Pictures

Student Civic Leaders address national issues on a local level

View All News