Yo Mama

Photographer Renee Cox empowers women of color by switching the script of the male gaze through her representation of the self, explains Miles Ladin ’90.

Her work is often iconoclastic, yet transcends simple polemics by portraying African Americans within an aesthetic of unshakable visual power. In the early 1990s, when I met Renee Cox in a master’s program at the School of Visual Arts, she was creating large photographic totems that crashed together both Christian and African iconography. Her work since then continues to affirm her own visibility in a Western culture that has historically minimized her presence.

In her iconic Yo Mama (1993, not pictured here), a nude Cox stands tall and upright, wearing high heels and holding her young son in her arms. The portrait affirms her role of mother and includes rather than precludes her ability to simultaneously own the role of sexual being. I include this powerful image in presentations when lecturing students on the difference between a selfie and a self-portrait. This brash, life-size photograph of a maternal yet sexual Cox is an eye-opener that subverts society’s expectations of motherhood.

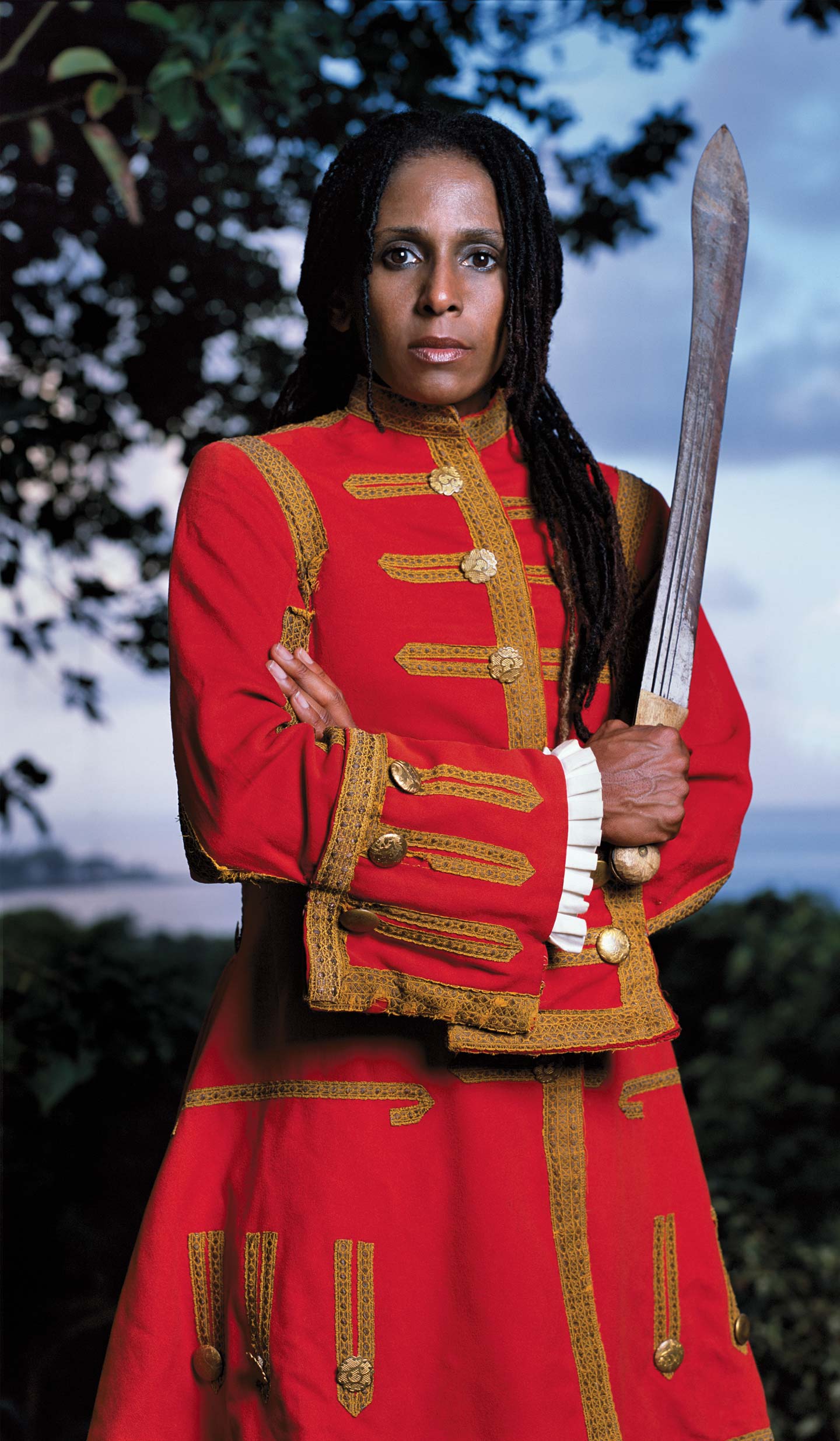

Cox has portrayed herself as superhero, queen, Madonna, warrior and even as Jesus herself. In 2001, this last incarnation brought the wrath of then-New York City Mayor Rudolph Giuliani and catapulted Cox to front page infamy. Lambasting her presumed sacrilege, Giuliani called for “decency panels” to take charge of New York City museums. Despite these pressures, Cox is as audacious as ever. Her latest body of work, Soul Culture, presents a kaleidoscopic assemblage of brown bodies that reference both Asian Mandalas and African culture. In this recent series, Cox continues to reimagine the visual landscape while celebrating her own brazen image.

Renee Cox visited campus for for two days, funded by the Visiting Faculty in Contemporary Art Endowed Fund in conjunction with “Perspectives on Photography” taught by professors Karen Gonzalez Rice

and Christopher B. Steiner.